18 Days Remaining:

Citizenship has always been a topic fraught with complications, especially from a U.S. perspective. Even now, citizenship is a topic that dominates the political sphere as well as tense conversations at the dinner table. Controversies surrounding citizenship, or lack thereof, are regularly catalysts for movements of all different kinds. Often lacking in the conversation of citizenship, however, are the people that are being talked about.

Many people throughout the world have had their entire existence depend upon the decisions of external forces/powers. This is a tale as old as our world: the fate of many rests in the hands of the few. Enter: The General Allotment Act of 1887, otherwise known as The Dawes Act.

Senator Henry Dawes of Massachusetts was the lead proponent of this piece of legislation, and of course, who it was named after. He held the belief, and wrote it into U.S. legislation, that the private ownership of property was a key component to civilization. In his words, the standards by which one could be considered civilized were to “wear civilized clothes, cultivate the ground, live in houses, ride in Studebaker wagons, send children to school, drink whiskey (and) own property.”

The beginning of the Act states its intention as to “provide for the allotment of lands in severalty to Indians on the various reservations, and to extend the protection of the laws of the United States and the Territories over the Indians, and for other purposes.”

Inherent in this first sentence is an arrogance of power and control. Who ever said that the land was anyone’s to give? The stipulation to these allotments? The denunciation and disavowing of one’s tribe. Only then could Native Americans whose ancestors had coexisted with the land for thousands of years be considered “citizens” of the country that had the history of its people in its soil.

So how did the Dawes Act play out? The Act stated that the head of each family would receive 160 acres of tribal land, and each single person would receive 80 acres. The title to the land would be held by the federal government, as the self-imposed ‘trustee’ of the lands and all its resources. After 25 years, citizenship would be granted to those that complied with the Dawes Act.

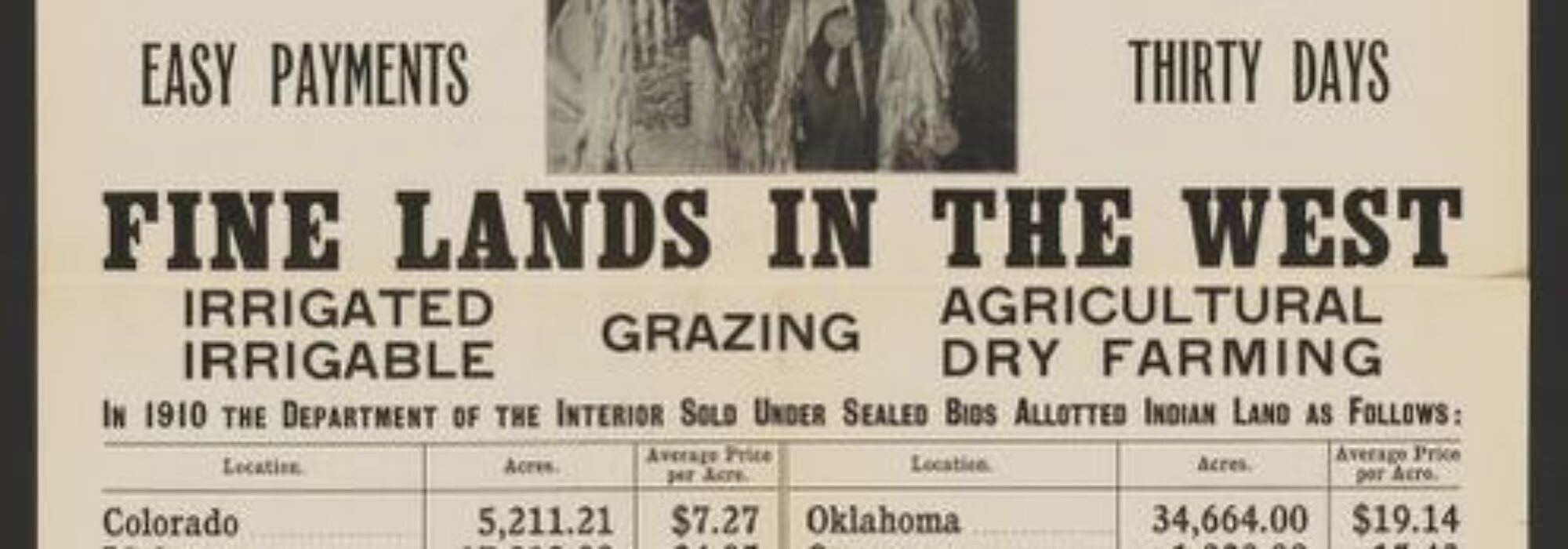

The choice was an impossible one that basically reiterated the belief system held in mainstream White U.S. society, that Native Americans could join it, but could not beat it. Any unclaimed or “surplus” land became the property of the United States government, and was sold off to non-Native persons.

Citizenship is all-too-often weaponized by those wielding power, and used as a bargaining chip that is centered around exclusivity.

The creation/passage of the Dawes Act meant the erasure of cultural and social traditions and the destruction to tribal lands. It enabled the continued desecration of systems that had been in place amongst tribal nations for generations. And, it legitimized a belief system that sustains to today that the United States Government has a right (endowed to it by nothing and no one) to give and take as it pleases, and as is advantageous to no one but itself.

“The earth is the mother of all people and all people should have equal rights upon it. You might as well expect the rivers to run backward as [expect] that any man … should be contented when penned up and denied liberty to go where he pleases.” – Nez Perce leader, Chief Joseph

Stay tuned for Day 17!